Reviews (863)

Run Hide Fight (2020)

Is it possible to keep a movie review separate from the filmmakers and their problematic aspects? Definitely yes, or rather it is possible not to notice them at all if the given filmmakers don’t try to show off. Unfortunately, the creators of Run Hide Fight couldn’t help themselves. Through most of the film’s runtime, they serve up a formally solid genre flick that chugs along well enough, with a bit of suspension of disbelief, i.e. if we turn a blind eye to the lapses in internal logic in the interest of spectacle. At times, it’s even likably emancipatory and progressive, while the binding of motifs of social hierarchy from high-school movies with a feminine variation on Die Hard also works (if you want to root for it). Understandably, there is nothing here that is comparable to Van Sant’s Elephant, Villeneuve’s Polytechnique, Johnson’s The Dirties, Poppe’s Utøya: July 22 or any other film that deals more in depth with only going through adolescence in a group of classmates, whether that is something from the numerous Scandinavian productions on this theme or the works of John Hughes. Run Hide Fight rather ranks among the genre flicks targeted at teenagers, giving them not only a combination of (melo)drama and trash, but also an engaging context, such as in The Hunger Games, How I Live Now, Danny’s Doomsday and tons of niche teen content on Netflix. And in this context, Run Hide Fight works fairly well. Thanks to its brisk pace and excellent female lead, it succeeds in distracting from the conspicuously half-baked nature of the screenplay and the minor red flags on the viewer’s part that come up in several scenes that could raise questions about the filmmakers’ intentions in terms of ideology. _____ Except the filmmakers didn’t want to stick only to subliminal messages and laid their cards on the table in the most stupid way – with an ostentatiously bombastic agitprop song plonked down in the closing shots. Then it comes as no surprise that the producers include not only the ultra-conservative talking head Ben Shapiro, but also the controversial producer Dallas Sonnier, who does not in any way conceal his right-wing attitudes. The above-mentioned elevation of the work above personal attitudes is not meant as a call for self-censorship. On the contrary, it merely points out the fact that thanks to such separation of the work from its creator, we can enjoy Polanski’s films, because he doesn’t turn them into pamphlets aimed at absolving him of his guilt. After all, even thorough familiarity with Sonnier’s problematic personality cannot similarly tarnish the qualities of his best-known productions, the original projects of S. Craig Zahler. That is because they are not conceived primarily in ideological terms and, furthermore, with their complex and multifaceted morals, they fiercely subvert strictly conservative and other glorifying interpretations. _____ Run Hide Fight does not give voice to any extreme or ultra-right views. It “only” foists on viewers the alibi-esque attitudes of the American gun lobby, which continues to promote lax gun-control legislation despite the terrifying number of domestic terrorist attacks and school shootings. The antagonists, and the main female protagonist, are depicted precisely in line with the standard arguments of conservative commentators, with the talking heads of Fox News at the fore. They always repeat that the shooters were evidently mentally ill and that no one is to blame for their actions, while on the other hand, they like to use the slogan that the only thing that can stop a bad guy with a gun is a good guy with a gun. Concealed behind these attitudes is an utter lack of interest in any sort of systemic solution at the expense of the current status quo. Run Hide Fight shows the same ignorance with respect to finding a way out of the crisis of violence and explicitly affirms these views. Therefore, one of the film’s juvenile terrorists takes the form of a ridiculously cartoonish madman, but it’s also why the central antagonist never reveals his intentions. None of them do, because the film’s creators have no intention of addressing the issue. Rather, they are content only with the excuse that he is a pompous sociopath who envies the popular kids for their sunny dispositions. The ideology is most conspicuously and atrociously manifested in the character of the terrorist-nerd. In the scene where he reveals his motivation, and especially in the protagonist’s reaction, the filmmakers deliberately downplay the issue of bullying, which was talked about as a systemic problem and trigger in regard to the Columbine shooting. After all, only the references to that massacre 21 years ago further confirm that the film’s creators strictly turn their gaze away from the breeding ground of contemporary violence in far-right ideologies and xenophobia. It would be desirable to refer to the above-mentioned limitations of Run Hide Fight in relation to other films on a similar theme and defend it as an escapist genre flick that doesn’t aim to say anything. But, again, its creators shoot themselves in the foot when, in an official statement from the Venice Film Festival programme, the director and screenwriter declare that, on the contrary, the film involved a discussion on a pressing current issue. With their genre fantasy completely cut off from reality, the filmmakers merely open themselves up to questions about responsibility, tact and the degree of empathy on their own part.

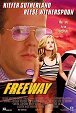

Freeway (1996)

Matthew Bright is either a cursed genius for whom there was no place in Hollywood, an irrational idiot, or just a filmmaking punk who has pissed on the classic standards of craftsmanship from on high. His filmography swings between the poles of the iconic underground Forbidden Zone and the star-studded melodrama Tiptoes. Freeway stands somewhere in the middle and shows Bright to be a diamond in the rough and subversive anarchist in equal measure. His directorial debut, which in its time was featured in the main section at Sundance, was produced under the auspices of Oliver Stone, who at the time was immersed in deranged visions of the outer fringes of America with projects like Natural Born Killers and U Turn. The crew was composed of a mix of dime-store fantasists reared by Roger Corman and renowned names, with Maysie Hoy at the fore, brought up by Robert Altman and Bright’s old buddy Danny Elfman. Despite the stellar cast, the film proudly shows off its punk pedigree with long, uninterrupted shots and exalted acting performances that evoke underground classics such as those of Christoph Schlingensief. After all, Freeway shares with Schlingensief’s projects not only an overarching principle of production, which we can summarise as “quickly, cheaply and furiously”, but also the basic concept of hysterically subversive appropriation of mainstream motifs and their emancipatory transference to a fringe environment, in this case the world of delinquents, streetwalkers and junkies. Bright’s paraphrase of Little Red Riding Hood manoeuvres between exploitation exuberance and soap-opera theatricality, while serving up an angry fairy tale that, with a feminist touch, takes into account traditional sexism and privileged arrogance. The journey of this Little Red Riding Hood with a lengthy rap sheet from a bleak home on the periphery, saturated with sexual abuse, drugs and social misery, to her grandmother’s home in a trailer park takes a lot of convoluted turns, including a reform school, that classic backdrop of movies about juvenile delinquents. But as in the story by the Brothers Grimm, the encounter with the wolf brings not only danger, but also an awakening and awareness of one’s own worth, not only in terms of how much to charge for a back-alley blowjob.

Sleepaway Camp II: Unhappy Campers (1988)

Instead of straightforward attractions, the first instalment of the Sleepaway Camp series was built on the environment of summer camps as the eternal hell of adolescence saturated with bullying and socialisation processes that crush individuality. In the second part of the series, the new creators (because, like Halloween and Friday the 13th, this originally indie genre franchise quickly fell into the clutches of a major studio) turned the whole concept on its head, conversely serving up a slick series of camp-themed murders, deliberately but unfortunately non-conceptually straddling the boundary between full-on slasher flick and parody. This time, the novelty in the context of the genre is not only the fact that it is clear from the beginning who the killer is, but also that it is actually the main character. The trend of elevating monsters to starring roles was introduced by the most popular franchises, especially A Nightmare on Elm Street, Friday the 13th and Halloween. However, the narratives of those films still mostly had a standard structure, where new groups of teenagers always developed into the central characters or the final girl from the preceding instalments continues in the hunt for the monster. Conversely, the second Sleepaway Camp shows, from the very beginning, the camp and its occupants through the eyes of the murderer, through whom they relate more to her reserved effort to both display and enforce exemplary behaviour from murder to murder. In the end, the film paradoxically again continues in the principle of the first part, in that it provides greater amusement through its overarching work with genre formulas than through its primary attractions. The slaughter of teenagers this time has noticeably more verve and explicitness, but by completely eliminating suspense from the film, these aspects became only mechanically arranged scenes without gradation or any deeper effect, as well as without sufficiently utilised exaggeration.

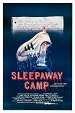

Sleepaway Camp (1983)

The Sleepaway Camp series, or rather its ’80s contributions, is a unique curiosity in the context of the contemporary wave of slasher flicks, as it deliberately plays around with the basic building blocks of the genre more than it offers direct viewing pleasure. The first instalment lags far behind in terms of the superficial attractions of slasher movies, when a significant part of the murders take place off screen or are only hinted at. However, it focuses more on the typical setting of groups of adolescents. Unlike other movies, however, the first Sleepaway Camp does not play an illusory game about tight-knit groups of adolescent kids and summer camps as places of cheerful frolicking, instead showing them as terrifying social petri dishes. It is one of the few ’80s films that do not gloss over bullying as an isolated prank, but takes it as its central theme, showing its systemic nature and, mainly, relating it to the hierarchical structures and power arrangements of children’s groups. Also, through the final denouement and anticipation thereof in the course of the movie, it’s impossible to shake off the impression that Robert Hiltzik, in essentially his only film, needed to escape from his inner anxieties brought on by adolescence and only due to economic concerns used the framework of a slasher flick to explore the subject matter, which could also have served for a much more concise and claustrophobic psycho(logical) horror movie.

Virgin Hunters (1994)

When a whole film is not more than the sum of its individual parts, but even comes out as less, there is a very good chance that the name David DeCoteau will appear in the credits. In the hands of another director, Virgin Hunters could have turned out to be a very entertaining blend of Tomorrow I’ll Wake Up and Scald Myself with Tea, Some Like It Hot, Terminator, ’80s teen comedies and ’90s silicone softcore erotica. A better screenplay would also have helped the theoretical result a lot, where, for example, humour would not be based only on embarrassing jokes, but also on the fact that DeCoteau kills a lot of potential with his characteristically ultra-cheap production. The scenes are simply first takes (not necessarily good takes, as indicated by shots where the microphone occasionally falls into the picture) and are done in large long shots, instead of breaking them up and giving them the necessary dynamics. On the other hand, the master of direct-to-VHS trash knew very well that he did not need anything more sophisticated or higher-quality to succeed or cover costs. A few sticky dreams evoking softcore sequences of nudity and the one boudoir-lit bedroom scene were enough for the target audience of boys just entering puberty. As is customary in the category of subliminal sexist indoctrination flicks, any deviation from heteronormativity is strictly rejected, so that unlike porn, the nightly rendezvous of co-eds in sexy lingerie never cross the line and, unlike Some Like It Hot, any gay allusions are immediately condemned as disgusting. The gender-specific upbringing of boys (not only) in the United States involves the belief that ambitious career women are uptight and it suffices to awaken passion in them so that they will cast off their nonsense and get back to where every woman supposedly belongs, which is in the wet dreams of inexperienced virgins.

Savage Harbor (1987)

Stallone and Mitchum together in the same film! Not Sly and Robert, but the first one’s brother and the other one’s son. Frank Stallone and Christopher Mitchum both so closely resembled their famous relatives that they became sough-after actors for low-budget trash flicks, which they willingly signed up for. The producers of those movies simply relied on the fact that customers of video rental shops would confuse the names and they could fob off a flick with a Stallone that, however, cost a tiny fraction of Sly’s blockbusters. Savage Harbor does not in any way deny this calculus, so we don’t concern ourselves much with the screenplay or with any other viewer attractions. When it comes to action, it’s not enough to marvel only at the extent of artless hollowness, but also at the strict adherence to genre logic, regardless of the production shortcomings. So, when the screenplay calls for the bad guy to shield himself from gunfire and there is only a chain-link fence, then he simply hides behind it. The whole film is similarly random, not only in the sudden eruptions of bullshit in the direction, but also in the dialogue, the screenplay and even the synopsis. A sailor on shore leave falls in love with a runaway prostitute and wants to buy an avocado farm with her, but her past catches up with her, so the sailor and his sidekick set out to look for her after returning from a six-month voyage. At its core, Savage Harbor is actually a variation on Popeye – the protagonist is a good-guy sailor who likes to feast on something green and wants the woman whom the villainous, obese antagonist wants for himself. This dreck, which didn’t cause much of a stir in video rental shops, has rightly sunk into oblivion, though when seen from the proper perspective, it does offer satisfactory entertainment, albeit mainly at the expense of the limited register of most of the actors (the best of whom turns out to be Greta Blackburn in the role of the good-hearted prostitute). After all, Frank Stallone recalls that when he watched the film with his brother at the time, they rolled on the floor laughing. In addition to the mighty mullets worn by the lead actors, the status of this bizarre curiosity is enhanced by the casting of the supporting roles. Besides Anthony Carus, a creditable portrayer of bad guys in the final years of the golden age of Hollywood, the former child star Lisa Loring, who once shone brightly as Wednesday in the classic black-and-white The Addams Family and here plays a stripper in love with Mitchum’s hero, deserves mention.

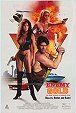

Enemy Gold (1993)

The Sidaris family fell into destitution. The central star of their seven previous films, as well as the systematically constructed universe bound to her, chose motherhood for a career and sent shockwaves through the world of magnetic tape. In addition to that, their trademark picturesque environments of sun-drenched beaches, scantily clad centrefolds and juvenile action not only got bogged down in repetition, but mainly lost their uniqueness. Whereas this combination was a spluttering novelty that could survive thanks to the global video market at the end of the 1980s, these Sidaris attributes were appropriated by the mainstream with the advent of the early 1990s as the most credulous, debauched and completely undiscerning era of pop culture. Recall that playmate Pamela Anderson shone in the third season of Baywatch in 1992, while shows like Tropical Heat and Renegade provided action amusements on the small screen, joined by Walker, Texas Ranger in 1993. The video market was also transformed, as younger predatory fish, with PM Entertainment at the fore, fought for viewers’ attention and well-established purveyors of trash such as Action International Pictures attempted to counter them with more expensive projects and the major studios were breathing down the back of everyone’s neck with their own straight-to-video productions. The confluence of these and other factors led to the fact that the Sidaris family business essentially tightened its belt and then transformed itself into the new production company Skyhawks Films (Malibu Bay Films remained only as a distribution company), and while the patriarch Andy gathered strength for more original projects, his son Christian Drew Sidaris followed in his footsteps. _____ In and of itself, Enemy Gold is not a disaster, though it’s nothing to write home about, either. In contrast to previous Sidaris films, it comes across as disturbingly modest, dry and futile. The photogenic exotica of Hawaii was replaced with generic exteriors from an audio-visual bank and the dirty realities of Louisiana. The non-stop promenade of characters and a variety of centrefold models was replaced by a constricted cast limited to seven characters and a few one-scene bit parts. Above all, the childish guilelessness almost entirely disappeared along with the playing with Bond-esque gadgets and remote-control toys and even all exaggeration. The overall pared-down nature of the production finally becomes apparent in the explosions and shootouts, as well as in the constituent locations of the film, hence the shift of the action in the second half to a forest, i.e. to an environment traditionally used mainly by amateur productions with zero budget. The only thing reminiscent of the old days of Sidaris movies is a few silicone ladies, boudoir-lit make-out sessions and an appropriately hollow script with obvious straightforward twists (the coincidences leading to the discovery of the treasure from the Civil War are outlandish). But it’s still not the bottom of the barrel (that would be the boring Savage Beach), but the bitterness of society and the film universe, which found themselves in limbo, hangs over the whole project. Julie Strain and Suzi Simpson greatly elevate the whole work idling in neutral, but they can’t save it. _____ In the context of the Sidaris MCU (Mammaries Cinematic Universe), we can refer to this film as the first title in Phase 3, following the example of categorising Marvel movies. This is defined by production under the banner of the newly established Skyhawks Films. Besides Sidaris’s loyal players, led by Rodrigo Obregón, only the worn-out Bruce Penhall remained from the main actors from the preceding phase. Following the example of previous projects, Enemy Gold was made as a dual production together with The Dallas Connection. When comparing it to this noticeably more ambitious second film, it seems that Enemy Gold was made a bit outside the framework for using the locations and actors, but the greater part of the funding was swallowed up by The Dallas Connection.

Fit to Kill (1993)

Andy Sidaris was always a visionary of mainstream shallowness. When he was just starting out in the field of television sports broadcasting, which won him an Emmy Award, he came up with the so-called honey shot, which long dominated that format. In Fit to Kill, he definitively codified jacuzzi aesthetics, which were subsequently taken over in the new millennium by reality shows in the style of Big Brother. His effort to continuously expand his own universe unavoidably resulted in a flick overflowing with characters from previous pictures. Besides the necessity of giving each of them a certain amount of space and including a few newcomers, that inevitably led to a frenzied mishmash. Under the weight of so many characters, the original world of centrefold agents and demonic bad guys, recalling the wet dream of an adolescent James Bond, the movie utterly sinks to the level of a soap opera in which the characters only loll around in the jacuzzi or on a yacht. Sidaris always pointed out that when writing characters, he proceeded based on the actors’ real-world skills, which explains why Don Speir pilots a plane in every film, Cynthia Brimhall sings some despondent hit, and Ava Cadell spouts some esoteric nonsense about relationships. The resulting lack of space then puts the newcomers in a dubious light, especially Sandra Wild, whose part is limited to answering telephones while standing topless in the jacuzzi. Fortunately, however, Sidaris again unleashed his laddish self (or rather immediate gratification of his id) so at times Fit to Kill is transformed into a catalogue of remote-control bimbos. In addition to boobs (predominantly silicone this time) and remote-control toys, there is a satisfactory amount of other popular things for adolescent boys, such as huge sunglasses and impractical yet very cool costumes, as well as some swastikas thanks to the plot about a diamond stolen by Nazis (the authenticity of the story is demonstrated by the fact that it is stored to this day in a box with a swastika on the inside of the lid). Julie Strain, who enjoyed her first role as a cunning villain so much that she became Sidaris’s mascot through the rest of their shared filmography, brings the necessary enthusiasm to the boudoir somnolence. The movie’s fun factor rises a lot in the climax, where there is finally some properly silly action when Sidaris artlessly edits together two locations that are obviously miles apart. In addition to that, Fit to Kill most effectively puts the impotence of Sidaris’s flicks on display. The need to get some honeydrippers in the film (which were usually invented and directed by his wife and producer Arlene) is covered in the script by simply having the characters, who are incompatible with the story, fantasise about themselves. That’s not even to mention Sidaris’s strait-laced heterosexuality, which goes against the otherwise overarching porn logic. Any two characters of the opposite sex begin to fool around at the drop of a hat (at least in a dream). But even though the female agents spend a lot of time alone in pairs lolling around or hanging out in the jacuzzi, crossing the lesbian line, which is such a typical feature of porn, is an absolute taboo for Arlene and her husband. _____ In the context of the Sidaris MCU (Mammaries Cinematic Universe), we can refer to this movie as the final title of Phase 2, following the example of categorising Marvel movies. The film was shot concurrently with the preceding Hard Hunted, to which it is connected in terms of plot by the central villain and several references in the dialogue. Unfortunately, due to the confluence of external factors, this second phase was terminated. The main reason for that was the pregnancy of Dona Speir, who quit show business entirely to raise her child. It is also the Sidaris family’s last more narrative-oriented project and the last of their films actually shot in Hawaii (with the exception of a few scenes from the very final conclusion of the Return to Savage Beach series).

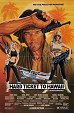

Hard Ticket to Hawaii (1987)

Those with acid tongues say Andy Sidaris’s filmography, or rather that of the entire Sidaris family, exhibits only diminishing returns. There is definitely some degree of truth to that statement based on the production values of his movies. His first two films were influenced by other producers and screenwriters, who enriched Sidaris’s centrefold visions with their contributions and thus improved them. But when this eternal prepubescent fantasist struck out on his own, he began to build his own universe, into which he gradually sank and he increasingly focused on its distribution at the expense of superficial attractions and exaggeration. Therefore, Hard Ticket to Hawaii, as the very first of his films linked by characters and setting, still abounds with more than a few viewer-gratifying elements and it is not undermined (in chronological viewing) by the triteness of the maestro’s trademarks. The peak of primitive genius lies in the stylisation of the movie’s world, which can best be characterised as impotent porn. Whereas plot, or rather events other than copulation, was pushed as far aside as possible in the porn of the time, Sidaris offers viewers another side of fairy tales for adults. His world is inhabited exclusively by Playmates and Penthouse Pets, shredded Adonises and cartoonish flunkeys (actually, it’s such an American-style gluttonous and hypertrophied live-action variation on the anime of the day, especially that of Reijo Matsumoto). Women never miss an opportunity to shower or change clothes, but when it comes to honeydrippers, everything remains modest from the waist down. The boudoir aesthetics of Playboy video compilations are combined with the style of tourism commercials, while properly exaggerated twists and burlesque pranks are injected into this surreal world. The protagonists’ clashes with the henchmen, with their unbridled excess and absence of proper choreography, can be compared to boys between the ages of six and ten playing army and the technical gadgets with which the agents and killers are equipped come across as cartoonish grotesques. Therefore, the insane subplot with a mutant snake infected with “toxins from cancer-plagued rats” doesn’t stand out from the rest of the film. Hard Ticket to Hawaii offers a deliberately overwrought and über-spasmodic spectacle that is concurrently guileless as well as healthily exaggerated. _____ In the context of the Sidaris MCU (Mammaries Cinematic Universe), we can refer to this movie as the introductory title of Phase 1, following the example of categorising Marvel movies. The three preceding feature-length films in Andy Sidaris’s directorial filmography comprise Phase 0, which is characterised by forming of the style and lack of links between the worlds of the individual films. Phase 1 is defined by the presence of the agent duo Donna and Taryn (played by Dona Speir and Hope Marie Carlton). Here, Sidaris himself very oddly tries to relate his own origins to the newly constructed world. In one scene, the characters admire posters for his previous films, mentioning that the main character of Malibu Express is their former fellow agent. It is not entirely appropriate to imagine the narratological causality of this apparent meta footnote, because it is as straightforwardly recombined as the rest of the fruits of Sidaris’s imagination.

Action U.S.A. (1989)

How the hell is it possible that this magnificent action flick has so drastically sunk into oblivion while every possible piece of dreck from the VHS era, where some desperate people chaotically wave their arms and someone occasional fires a gun, are seen as the heartbeat of a generation. Well, the answer is relatively easy. The reason consists in the fact that the film’s creators put together the best action sequences for their grandiose stunt showreel, but somehow didn’t bother with distribution. The directorial debut of the self-proclaimed stunt legend John Stewart is lightly based on the buddy movies of the day featuring black and white lead actors, but unlike the classics of the genre, such as 48 Hours and Lethal Weapon, it doesn’t bother with developing the characters and their dynamics, because the screenplay is appropriately makeshift and serves only to very vaguely lay the groundwork for the next breakneck action sequence. Fortunately, the movie does not take itself seriously at all, so the characters and individual scenes rather come across as caricatures of genre clichés. Whereas the more recent trend is to incorporate action into drama and to connect it to the characters so that it is not merely an attraction, but also something that draws viewers in, Action U.S.A. glorifies the tradition of spectacular stunts that put the plot on hold and make viewers marvel at what the obviously suicidal stuntmen are going through to get the wow effect. Today, this style is completely out of fashion, but in the 1980s, whole movies such as the showreel Fire, Ice and Dynamite and series like the iconic The Fall Guy were built on it. Stewart and his sidekicks can’t compete with genre legend Hal Needham and his Hooper in terms of either budget or spectacle, but they definitely offset that deficit with the dangers that they face, as well as with the guilelessness with which they make their own self-realisation the priority in the film’s logic. Viewers should not shake their heads at the fact that whatever the car crashes into will explode, but instead should simply accept this fact and admire the outsized explosions and the ambition to risk one’s health and the equipment in the interest of the most effective shots. In this respect, Action U.S.A. offers amazement and rambunctious entertainment like few other films.