Reviews (863)

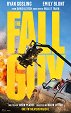

The Fall Guy (2024)

Ryan Gosling is the action hero that modern masculinity needs, and this film is a magnificent culmination of the roles that he has played so far and his image. Instead of bombastic macho tough guys, here we have a guy who can handle wild physical challenges, but he also knows how to come to grips with his emotions (even if it’s only by listening to plaintive songs in his car) and can be sensitive, supportive and friendly towards others while taking himself with a sense of detached humour. And on top of that, he’s also both hot and adorable. In addition, The Fall Guy offers up a bombastic tribute to stunt work that comprises a grand culmination of the work done by the stunt and choreography group 87eleven, or rather its production division, 87North. Besides the trademark style of fight choreography, the filmmakers fortunately focused primarily on the logistically more challenging aspects of stunt work with automobiles, explosions and collisions, and every possible kind of fall, which they execute not only for the camera, but also for the narrative. All of this is done mainly with the aim of lobbying for the rectification of the nonsensical neglect of stuntpeople at the hands of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. (However, it could possibly be argued that the Academy doesn’t overlook stuntpeople because it would want to somehow draw attention away from the behind-the-scenes magic of film, but solely because most members of the Academy don’t understand the industry and the results of voting would correspond to that, as is the case with the animation category.) In light of all of that, The Fall Guy also works as a refreshingly exaggerated romantic comedy that takes the female point of view rather than the usual male perspective. Though it’s true that the film is somewhat handicapped by the uneven screenplay and exceedingly obvious utilitarianism of the individual peripeteias, which serve as an excuse for staging particular bits of choreography, this is offset by the fact that the filmmakers know how to shoot everything with maximum effectiveness and entertainment value, which is not true of the film’s spiritual ancestor, Hooper (1976), by the first stuntman-turned-director, Hal Needham.

The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai Across the 8th Dimension (1984)

Wes Anderson likes this. That’s a fact. The renowned offbeat filmmaker has admitted that he counts himself among the avowed fans of Buckaroo Banzai, which shouldn’t come as a surprise at all. We can find echoes of the film’s team of eccentric characters facing absurdly exaggerated obstacles with a straight face not only in Anderson’s direct homage, The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou, but also in all of his other films. We can even say that Anderson’s first films, Bottle Rocket and Rushmore mirror the desire to live life along the lines of Buckaroo Banzai in the dull real world and with the same sincere naïveté that we experienced as young boys founding our own version of Our Gang. Starting with The Life Aquatic, Anderson finally had the means and the renown that allowed him to subsequently do nothing else but aesthetically polished paraphrases of Banzai-esque team-based movies freed from the bonds of reality. ____ If we leave aside the waggish conspiracies of fans and filmmakers who highlight the film’s incomprehensible and offbeat nature, Buckaroo Banzai comes across as a live-action antecedent of Adult Swim’s animated series, especially the channel’s retro-meta productions. Like Sealab 2021 and Mike Tyson Mysteries, Buckaroo Banzai is based on the comic-book ethos of classic team-based series such as Jonny Quest, G.I. Joe and Scooby-Doo with their trash premises and sincere naïveté. But its ethos also links it to later projects like Mister T (and perhaps even Chuck Norris: Karate Kommandos), which stood on the cult of personality of the central character, the semi-divine leader of the team. But unlike the stoner logic and subversive absurdity of Adult Swim’s productions, W.D. Richter and Earl Mac Rauch took the route of intellectual-nerdy camp. They thus take delight in the highly convoluted histories of the film’s world, characters and individual artifacts, and revel in references to the entire field of fantasy and pop culture, ranging from Thomas Pynchon and Orson Welles to rotoscopes and B-movie sci-fi to martial arts and pulp comic books. The whole project is imbued with a sense of tremendous exaggeration, as well as with the joy that comes with being able to childishly goof around in its world, leaving aside needless rationality. Thanks to that, this commercial failure became a beloved cult classic that appeals to the same group that its creators came from. The pastiche of cult movies and trash flicks itself became a cult movie that stimulates its viewers’ desire to again be young boys who thumb through comic books and hope that someday they can the sidekicks of their favourite heroes. But in this case, they rather know that’s not going to happen, but it’s fun to give it some thought. Buckaroo Banzai is thus actually Star Trek and Galaxy Quest rolled into one, though its fandom revolves around the meaning of watermelons instead of wildly overclever theories.

Armoured Car (1929)

In a period enthralled by Tom Cruise’s stunts, Armoured Car offers a curious reminder that, despite the post-revolutionary moaning, action escapades were cultivated in Czech cinema in the early days. In this case, however, this is true only if we allow ourselves to give the local industry credit for the filmmakers and other creators who identified as Germans. On the other hand, however, we have to admit that whereas Cruise, Jackie Chan, Belmondo and other later stars have been able to work dramaturgically with viewers’ amazement elicited by grandiose physical feats, here the bombastic acrobatic performances of the lead actor, blown up to superhuman proportions by movie magic, are rather unexpected eruptions of energy in a mostly sedate pulp story, though it’s a story that is likably kept afloat by campy exaggeration aimed at dime-a-dozen clichés.

Werner - Gekotzt wird später! (2003)

Careless milking of the franchise by ticking off a list of mandatory ingredients with repetition of things we have already seen. In the better case, it can be seen as misguided ambition to attract new viewers to the Werner brand; in the worse case, it shows the advancing senility of a once likably impertinent pop-culture phenomenon.

Werner - Eiskalt! (2011)

The would-be impertinent and rebellious Werner franchise gets the worst possible ending with this feeble-minded monument dedicated to itself and its creators. Rötger “Brösel” Feldmann perhaps sees himself as a comic-book Mick Jagger in the automotive DIY world of Mad Max, but unfortunately he is merely a German cartoonist (albeit an artistically gifted one) who has succumbed to the illusion of his own cult of personality. The penultimate Werner movie was annoying in its repetition of what had already been seen in the previous films. But this, the perhaps definitively last instalment of the franchise, blatantly materialises the sad gerontological ambition to relive the supposed highlights of one’s youth. In order to keep the desperation at a high level, the film has to take a bitter swipe at current popular trends in the comic-book scene and acting roles for all of the creator’s friends, who naturally have no acting skill whatsoever. And everything is topped off with an irrationally illusory storyline in which the protagonist/creator effortlessly wins the favour and body of a run-of-the-mill playmate.

Monkey Man (2024)

In the field of action movies, Monkey Man is a revelation similar to what the first John Wick was in its time, but it gets essential extra points for having a lot of heart. An extremely likable aspect of Monkey Man is that this straightforward and formalistically well-worn revenge flick packed with fighting was made as its creator’s dream project, making it even more resistant to all kinds of adversity. Dev Patel, whom everyone sees as an actor who plays sensitive characters, returns here to his adolescence, when he practice taekwondo at the competitive level. Or, as the case may be, he goes even farther back in time, when he enthusiastically watched the physically captivating and emancipatory films of Bruce Lee. In addition to that, he also makes good use of his thorough knowledge of martial-arts action films and their Western, Far Eastern and Indian milestones from the decades that followed. However, Monkey Man offers more than just enthusiastic references, which Patel acknowledges and highlights. He is able to self-sufficiently use those references as a foundation and push them further – not necessarily through any sophistication or purposeful bombastic radicalism, but through the long built-up desire to show what he has within himself. The notional boxing ring of the action genre has been dominated in recent years by the 87eleven stable, which still manages to bare its teeth with each new John Wick movie, but because its style has become the mainstream standard, it already seems noticeably hackneyed and worn-out. In this analogy, Patel and his team represent those young, aggressive and hungry outsiders whom no one believes in at the beginning, but who then capture the hearts of the whole crowd by the time the fight is over. Patel’s combination of Bollywood colourfulness, eclectic multiculturalism (in terms of aesthetics and genre, as well as the traditions of martial arts) and pervasive enthusiasm would suffice to make Monkey Man something special and give it the decision on points. But there is also the brutal choreography and, primarily, the extraordinary camerawork by Stephen Renney, newly promoted from stuntman to camera operator, which tear the established competition to pieces with their aggressiveness, rawness, uncompromising physical energy and wild dynamism.

Godzilla x Kong: The New Empire (2024)

The Hollywood blockbuster has finally developed into the form of pure camp. For many years I dreamed that a movie consisting of pure, unadulterated silliness would come along and displace the would-be sombre and fanboyishly over-clever spectacles. The New Empire is aware of its own silliness and roguishly cranks it up. So here we have phantasmagorical technobabble, exceedingly stupid human characters, superficially calculated twists and paper-rustling peripeteias, but everything fits beautifully into the overall colourfully crazy world where the boneheaded alternative hollow-earth theories become their own absurd caricature. This papier-mâché puppet theatre then gets perfectly trampled by a full range of giant monsters. The human characters are relegated solely to the role of narrative crutches that bridge the monsters’ individual storylines, for which purpose they utter absurd nonsense. The monsters have finally have broken free from western individualism and human exclusivity. The New Empire turns the genre’s perspective back to its Japanese kaiju roots, thus making the titular titans the main characters and bearers of both the narrative and the overarching point of view. The character that guides the audience’s perspective is not one of the ant-like humans with their insignificant plans, but a mini-Kong. Of course, I remember almost nothing about the film just a day after the screening, but I know that during my ride on this roller coaster, my eyes were glued to the screen just like when I saw the goofiest kaiju movies from the delirious sixties. P.S.: My perverse dream is for Werner Herzog to deliver the special commentary on the Blu-ray release.

Love Lies Bleeding (2024)

Just go see this film and avoid the trailers, which unfortunately are spoilers and could raise misleading expectations. Love Lies Bleeding has a neo-noir heart pumping blood to the organs of post-modern shifts that include a rural desert setting, refreshingly subtle 1980s retro stylisation (no kitsch as in Stranger Things) and a crowning gender+queer twist. Fortunately, there’s no cartilaginous connective tissue here, as everything is driving by the massive musculature of captivating physicality, vivid stylisation and a distinctive creative perspective. Rose Glass confirms that she belongs among the makers of intensely sensory films, thus expanding this hitherto male-dominated club (with Gaspar Noé, Jonas Åkerlund, Jonathan Glazer and Harmony Korine at the fore) with a fresh, unique voice that in certain respects is more down to earth while at the same time managing to incorporate a much broader range of motifs. Like the other aforementioned filmmakers, Glass works with exaggerated visual stylisation, highly distinctive characters and a modern visuality unbound by the limits of mainstream hyper-realism. She spins the symbiosis of these elements into a captivatingly physical experience for viewers. Accordingly, her work with noir is not limited to the usual formulas such as the concept of the femme fatale or the narrative structure of an investigation. She goes to the instinctual and dark essence of the genre, even diving into the dark, viscous waters of Southern Gothic. She highlights passion, obsession, the dreadful appeal of violence and the power of the manipulativeness of blood ties. She also manages to weave into the main story a number of complementary motifs, from the monstrousness of ego to the myth of the land of limitless opportunities. In doing so, however, she still tells of love and its power to crush us and everything around.

Poor Things (2023)

Poor Things is a tremendously charming and wildly playful cinematic bildungsroman that demolishes gender roles and patriarchal fallacies with unbridled childlike verve, while grandiosely revealing their absurdity. Whereas Barbie was built on a shared sisterly sigh with a smile and remained in the realm of consumerist conformity while glorifying plastic kitsch, Poor Things offers up a lavish and iconoclastic riot grrrl pamphlet with a likable pout. Bella Baxter is a captivating, monstrous role model. Her journey through the world inevitably leads to her coming of age, but not in the sense of abandoning immediacy and committing herself to accepting the lot in life that others have laid out for her. Bella gets to know the world with its painful paradoxes, but she does not let herself be constrained by those around her and can conversely build places of personal freedom within herself and in her immediate surroundings amid all of the social nonsense. The film incorporates all of this into a sort of Art Nouveau ornament that is simultaneously delightfully beautiful and unavoidably bittersweet, as the steampunk stylisation and grotesque derangement constantly highlight its fantastical and thus unrealistic essence.

Early Birds (2023)

This Swiss Thelma and Louise is a by-the-numbers Netflix production, a localised genre movie with solid craftsmanship and the promise of being atypical, but it comfortably remains in the realm of the commonplace while using variations on motifs and sequences from various cult films. So it is actually an example of “If the competition doesn’t give us a popular classic, we will produce our own knock-off in Europe, thus also fulfilling the requirements for contingent EU projects”.