Reviews (840)

Summer (2018)

This damned hot summer can’t be over soon enough. But in the case of Kirill Serebrennikov’s Summer, I’d be happy for it to last longer. This is despite the fact that it basically consists of a story-less series of musical performances by obscure Russian bands and partially animated musical sequences (which, conversely, feature hits by famous Western musicians). The burgeoning love triangle has a certain dramatic weight, but due to how loose the relationships between the characters are, it cannot have very painful consequences. Nor does the apparatus of the state put any serious pressure on the artists. The bohemian rockers encounter officers only once and deal with censorship easily and with humour. Despite that, we are constantly aware of the danger faced by the free environment that the protagonists have created around themselves in a country that is not free and the tone of the narrative gradually changes from the initial summer contentment to a melancholic premonition of an impending downfall. The final scene, which sums up this fleetingness of life with the aid of two blunt titles, is unbelievably powerful and timeless. ___ Summer is a film in which, as in Russia (or, for that matter, Czechoslovakia) almost nothing happens in the early 1980s. Just repeat the official government actions and speeches, always captured here somewhere in the background on a television screen, with which the regime shapes its (self-)image and maintains the status quo. Rock music, whose lyrics are about free love, alcohol and rebellion against the system, naturally disturbs this order. While musically it mainly involves (progressive and indie) rock or New Wave, the film is a somewhat punkish affair in terms of narrative, which adheres to most of the principles according to which drama should be structured. The rhythm is set by the songs rather than by plot twists. When the film loses its breath, one of the characters, who communicates with other inhabitants of this fictional world as well as with the viewers (to whom he continually announces that what we have just seen never actually happened), helps it get a second wind. However, it is seductively easy to get carried away by the narrative thanks to the film’s tremendous spontaneous energy, catchy songs, numerous outstanding and probably labour-intensive audio-visual ideas (the film’s highlights include the covers of cult records “coming to life”) and, of no less importance, the black-and-white camera work, which shifts from character to character in long shots with a superb intra-shot montage and, together with the songs linking the individual scenes, contributes to the impression of a smooth flow of events. ___ I realise that the film borders on being too dramaturgically lax, that it does not have to so thoroughly take on the cyclical repetition of certain situations that were typical of socialism, that the characters do not undergo any fundamental development and that the end could occur at virtually any given moment (it would have made perfect sense to me if the credits ran after the film appears on the screen and immersion in the sea). I therefore understand that Summer can be an arduous experience for viewers who do not see it from the first few minutes. For me, who had goosebumps even during the opening song (and then several more times after that), it was a totally liberating experience and one of the most accurate cinematic depictions of everything that I associate with summer. I would like to experience a summer like this every year. 90%

The Girl in the Spider's Web (2018)

If I didn't have a weakness for Lisbeth Salander and Claire Foy (and the criminally underused Vicky Krieps), I would rate this film more harshly. I don’t mind that the filmmakers have definitively turned Lisbeth it into a comic book superheroine who treats wounds with superglue, snorts a crushed amphetamine tablet to get up, can move from place to place at lightning speed and needs less time to hack the NSA than to make coffee for an ordinary mortal (Larsson’s trilogy was already headed in this direction). The problem is how they slapdashedly modified the plot to be substantially more layered with multiple perspectives taking into account (and alternating with) the work upon which it is based and the manner of storytelling. Events are connected to each other in a terribly careless and repetitive way, based on the same pattern (someone tries to kidnap/kill someone, that person is captured/escapes and around we go again). Despite signs of psychologisation (Lisbeth’s trauma due to her sister’s betrayal), the characters behave as if they are in a run-of-the-mill action film and their foolish decisions are too frequently not fatal for them due only to fortunate coincidences and magically flawless timing. The visual style, derived from Scandinavian noir and punk as well as S&M aesthetics and merely copying Fincher and Alvarez much more than the slow revealing shots evoking unease and unpleasant feelings (such as the first one after the Bond-esque opening credits), uses fast, chaotic cutting that buries the entire atmosphere. The director is apparently most “at home” during scenes with elements of horror, which make up the only aspect that is not as painfully generic and interchangeable as the rest. I would be glad to see Claire Foy again in the role of Lisbeth Salander, but not in a film that most reminds me of the feminist answer to Crank. 55%

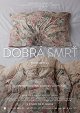

The Good Death (2018)

The Good Death is a documentary portrait of an English woman who intends to undergo euthanasia. Seventy-two-year-old Janet does not want to wait until her unfortunate health condition, caused by hereditary muscular dystrophy, deteriorates to such an extent that she becomes completely legally incompetent. She would lose the ability to make her own decisions supported by clear, rational arguments. She is not afraid of death. She has accepted it just as she previously accepted her illness and the fact that life is not fair and that it is necessary to deal with it in accordance with her current options (unfortunately, the film does not elaborate on the fact that not everyone in her situation has the same options and a "good" death is a kind of privilege, but I understand that such an exploration would be a detour from the direction in which the film’s attention is focused). While Janet determinedly and resignedly approaches the day when the pentobarbital solution will end her suffering, we follow in parallel the story of her son, who suffers from the same disease and anticipates the same fate.___Despite the apparent similarities in the way both social actors are filmed, however, her son’s storyline is more hopeful, as Simon is involved in research that could lead to the discovery of treatments for the currently incurable disease. The impressive visual concept, the use of contrasts and parallels, the heroine’s poetic off-screen commentary and the unforced mise-en-scène to illuminate Janet’s previous life keep the film in the space between procedural drama and open-minded consideration of how death is “natural” (two religious commentaries on euthanasia were typically included in the film – according to one, God should decide on our existence and non-existence; according to the other, God does not want us to suffer and it is therefore acceptable if we decide to end our own lives). Despite the occasional intensification of the melodramatic level through the use of mournful music and the aestheticisation of actions connected with one’s final affairs, the film does not resort to the exploitation of human misery. It is shot with great humility and understanding both for those who have decided to leave and for those who remain. 70%

The Haunting (2018) (series)

When you accept from the beginning that Mike Flanagan (see also the excellent Oculus) is using a horror framework for the purpose of relating a suspenseful narrative about dealing with family traumas, finding trust (the story of a woman who no one believes repeatedly falls victim to attacks, which is very up to date), overcoming fear and the search for a home (i.e. unlike in other horror films, family history does not serve only as pretext for the scares – it is the main subject; fear comes from outside), you can then enjoy this psychologically compelling drama with its layered narrative structure and smooth (visual and audio) transitions between the past and present, facts and imaginings, as well as “old school” scares, based on the intra-shot montages and disturbing movement in different parts of the picture. Though some scenes are shot in a rather run-of-the-mill manner (shot/counter-shot dialogue scenes) and the conclusion with a loosely formed metafiction level is somewhat negatively affected by excessive ambitions and runtime (each of the episodes, usually bound to the point of view of one of the main characters, has its purpose, but many of them could easily have been shorter), The Haunting is excellent overall in terms of acting and directing, and one of the most pleasant surprises of this year among series. The sixth episode, consisting of several multi-minute shots that are complex choreographically and in terms of meaning, ranks among the best that high-quality TV has to offer with respect to craftsmanship.

The Other Side of the Wind (2018)

Jake Hannaford, a passionate hunter of Irish descent, as well as a chauvinist and racist, is not so much an alter ego of Welles as he is of John Huston. The Other Side of the Wind captures the last days of classic Hollywood, or rather the decline of the world represented by macho Huston-type patriarchs. Because of her indigenous origins, Hannaford sees the lead actress of his film as an exotic exhibit and mockingly calls her “Pocahontas”. The actress initially reacts with hateful looks and later vents her frustration by shooting at figurines. Hannaford’s publicist, based on film critic Pauline Kael (who couldn’t stand Welles), is not reluctant to engage in open verbal confrontation with the director when she repeatedly points out the macho posturing that he hides behind. The women defend themselves and the men are not happy about it. ___ By giving the female characters more space and enabling them to give expression to their sexuality, Welles comes to term not only with Hollywood, but also with his own legacy. Like late-period John Ford, whom Welles greatly admired, he critically reassesses the themes of his earlier films. At the same time, however, doubts arise as to whether the way in which Oja Kodar’s character is presented in Hannaford’s film (sexually aggressive, captivating an inexperienced male protagonist) also says something about Welles. ___ Hannaford's unfinished magnum opus is clearly a parody of the works of American filmmakers who during the New Hollywood era responded diligently to European works by shooting pretentious and incoherent would-be art films packed with eroticism and conspicuous symbolism. More or less naked, beautiful and young actors wordlessly wander around each other in dreamlike interiors and exteriors. It doesn’t seem to matter that the characters don’t follow the sequences of Hannaford’s film in the right order (if anyone actually has any idea what the order is supposed to be). As Welles divulged in an interview, he shot the film with a mask on, as if he wasn’t himself. Therefore, why should we associate with him what Hannaford’s work says about women and female sexuality? ___ The parodic imitative style, which was not peculiar to Welles, was due also to the raw, intentionally imperfect hand-held shots from a party, reminiscent of the then fashionable cinema-verité. Completed long after Welles’s death, the film is basically a combination of two styles that Welles would not have employed. The question of who Jake Hannaford was (like the question of who Charles Foster Kane was in Citizen Kane) is less relevant in this context than the question of who the creator is and who is imitating whom, which Welles quite urgently asks in the mockumentary F for Fake, which, with its fragmentary style, has the most in common with The Other Side of the Wind. ___ For example, Peter Bogdanovich, who was considered to be an imitator of Welles in the 1970s, plays Hannaford’s most diligent plagiarist in the film. The defining of his character through imitation of someone else, however, is done ad absurdum, when he occasionally begins to imitate James Cagney or John Wayne in interviews with journalists. Though Welles incorporates media images of influential figures into his film, he also ridicules them as improbable and untruthful. All of these contradictions could be part of an effort to offer, instead of the retelling of one person’s life story, an expression of doubtfulness about the ability to recognise who someone really is. ___ Though, thanks to Netflix, Welles’s film can theoretically be seen by far more viewers than would have been possible at the time of its creation, the manner of its presentation by the streaming company recalls a moment from Hannaford’s party, when the producer lays down reels of film and says to those interested in a screening, “Here it is if anybody wants to see it”. Netflix helped to finish the film and raised its cultural capital by presenting it at a prestigious festival, and then more or less abandoned it, as if cinephiles who love more demanding older films were not a sufficiently attractive audience segment. ___ With Welles’s involvement, the film, which was completed 48 years after it was started, would have perhaps been more coherent, had a more balanced rhythm and conveyed a less ambiguous message. At the same time, however, all of its imperfections draw our attention to its compilation-like nature, or rather the convoluted circumstances of its creation – we think about who is in charge of the work, who created it (perhaps Jake Hannaford, whose “Cut!” is heard after the closing credits) and what it says about him, which was probably Welles’s intention. The Other Side of the Wind is a good promise of a great film. 80%

Tomb Raider (2018)

Next to Wonder Woman, Lara comes across as a poor relation (perhaps producers perceive gamers as a weaker audience than comic-book readers). Tomb Raider offers a total of four environments (London, Hong Kong, an island, a tomb), no spectacular action scenes with the exception of the waterfall, and basically just one (rising) Hollywood star. In the context of the efforts to create a full-fledged action heroine, however, it represents a small degree of progress. Lara Croft is absolutely believable as portrayed by Alicia Vikander, who has natural acting ability. The pair of screenwriters (Geneva Robertson-Dworet also wrote Captain Marvel) did not engage in experimentation, instead offering a traditional origin story that clearly introduces non-gamers to the world of Tomb Raider and gives gamers a satisfying portion of backstory and a number of direct quotes from the game. Lara is introduced to us by the pair of opening action scenes as a woman who does not excel through tremendous physical strength, but through her ability to come up with clever solutions to problems. In both cases, she fails anyway. It is only after she actively resolves here “daddy issues” that she becomes a strong and self-confident (though not fearless), yet relatively credibly vulnerable action heroine. One gets the impression she has always had all of her presented abilities, some of which she owes to her father (problem-solving, archery), but that she only lacked inner balance, as she had no father figure in her life. In this respect, this outwardly progressive film is terribly traditionalist (actually in a similar manner as The Last Jedi – substitute Dominic West for Mark Hamill and you get the middle part of the film). However, the family storyline, primarily presented through flashbacks at first, is incorporated well into the main narrative, driving the plot and explaining the heroine’s motivations, while helping to bridge longer periods of time when the characters are moved to a different location. When it comes to any given scene’s contribution to the narrative, Tomb Raider is above reproach. There are almost no dead spots when we would lose interest in what happens next (Nick Frost’s cameo could have been shorter, or deleted). Everything is nicely connected and all of the parts fit together, though perhaps too smoothly and straightforwardly. The action scenes are sufficiently diverse and boldly reminiscent of the video game (and demonstrate how Lara improves herself in individual areas – hand-to-hand fighting, escaping from pursuers, jumping long distances) and the pace does not slacken. Just as in The Wave, Uthaug displays flawless mastery of his craft and knowledge of the principles of classic Hollywood storytelling. Within the action genre, that is not a bad thing at all, but I hope that the sequel, for which the conclusion of this film somewhat long-windedly and too obviously lays the groundwork, will not be as exceedingly cautious. 65%

Tully (2018)

Tully is a film at the midpoint between the best and the worst of which Jason Reitman is capable. Charlize Theron excels in the role of an exhausted mother of three children whose life has been reduced to mechanically repeated diaper changes and breastfeeding. Thanks to her performance, situations experienced and measured direction, we experience her fatigue, we understand her postpartum depression, and we feel tremendously relieved when Tully appears at the door. The magical nanny answers the (never-posed) question of what Mary Poppins would look like if she were a millennial and changes the film’s genre from a social tragicomedy that is clearly targeted in terms of narrative into an ambitious magical-realistic statement on losing faith in your sense of you are and what you are doing. As in the appalling satire Men, Women and Children, Reitman succumbed to the temptation to offer us grand, timeless ideas in addition to the minor dramas of ordinary people. In his concept, however, these are comically simplified and sugar-coated for easier digestibility (“A Spoonful of sugar helps the medicine go down”) and their presence in the story is justified by a terribly shaky narrative structure, the overbearing revelation of a predictable plot twist to the satisfying resolution of all other problems (the heroine’s unfulfilled career ambitions, lack of funds, her son’s autism). The end of the film, whose creators got a bit lost on the way from point A to point B, then offers a resolution, albeit through something that has not been presented as a problem so far (the involvement of the husband in taking care of the household). With its utilitarian approach to the characters, Tully is actually a terribly cynical and insincere film, despite its authentic beginning. 55%

Under the Silver Lake (2018)

This neo-noir mashup will most probably anger even more people than The Image Book (because more moviegoers will go to the cinema to see it because of Garfield). Rather than creating something original, both films are based on recontextualising earlier media content and seeking hidden meanings in pop culture, which represents the basic frame of reference in Under the Silver Lake. Everything refers to something that someone else invented in the past. There are no originals, only copies and rewrites. Therefore, the story has to be set in Los Angeles, a city that has played a role in so many films that it has become a remake of itself. Mitchell’s third film holds together thanks to its absorbing atmosphere at the boundary between Vertigo and Chinatown and its pseudo-detective plot. It unfolds in such absurd, totally Lynchian mindfuck ways that instead of providing satisfaction from the uncovering of new contexts, it brings only gradually deepened frustration. Both for us and for the main protagonist, a paranoid slacker like from a nineties indie film, it almost involves two and a half hours of a delayed climax (the only satisfying interaction takes place during the prologue). Throughout its runtime, it is also immensely entertaining, while being a deferential and cunning pastiche of classic and post-classic noir films (and the music from such films), most of whose “shortcomings” can be interpreted as conscious and ironic work with certain conventions and stereotypes. For example, we can understand the reduction of the female characters to more or less passive objects as a critique of the “male gaze”, as that is precisely how the mentally immature protagonist, whose perspective the film thoroughly adheres to throughout, perceives women based on their media representation in films by Hitchcock and others. Under the Silver Lake is an ambivalent postmodern work which, thanks to its lack of a centre and its solid structure, succeeds in expressing the confusion of young people who try in vain to find some sort of higher meaning in all of the stories obscuring their view of reality. For me, it was one of the most entertaining movies of the year, but there is roughly equal probability that you will hate it with all your heart. 85%

Utøya: July 22 (2018)

I believe that a thoughtfully enriching and formally courageous film can be made about the events in Norway seven years ago that not only leaves viewers shaken, but also forces them to think. Utøya: July 22 is really not such a film. Though I appreciate that its makers wagered predominantly on the realistic motivation of the scenes (which, however, is somewhat superfluous in a film with fictional characters), that in itself is not a guarantee of a good film. On the contrary, it leads to the fact that most of the film’s runtime consists of long, suspensefully simple shots of several characters hiding and sitting tight somewhere in the forest or under a rocky cliff. Furthermore, any authenticity is demolished by tasteless melodramatic crutches (a mother calling her dead daughter, a micro-plot with a boy in a yellow jacket) suggesting that the main and perhaps only (cynical) ambition of the film’s creators was to wring some emotions out of the viewers, to claw at their souls a bit by exploiting real terror (after all, this intention is indicated with a certain guilelessness by the sentence that Kaja delivers at the beginning while looking at the camera when she calls her mother: “You will never understand, just listen to me”). But the narrative is too straightforward (for proof that this can be done more inventively, see Van Sant's complex Elephant) and there are too few variables at play that would draw us into the story, so Utøya does not work even as an “adventure” survival horror movie. We may ask ourselves whether Kaja will survive or not, whether she will find her sister or not, but that’s all. Poppe relies on our connection to the protagonist, but forgets that the film is not a video game in which fear for the character’s life enhances the player’s control over her actions. As Son of Saul recently showed, it is possible to hold our attention without letting us catch our breath in the present moment while also making a complex statement on a particular tragedy. By contrast, Utøya is a paradoxical reconstruction of an event about which we learn almost nothing, with the exception of the opening and closing explanatory titles. For me, this is a prototype of a useless film without value added, which was made mainly to provoke a media response. It is a film in which it is possible to admire the athletic performance of the leading actress and the cameraman (even though the personalised camera work, which sometimes reacts to the surrounding stimuli independently of the characters, creates the misleading impression that we are watching scenes composed of found footage). 50%

Vice (2018)

When Christian Bale thanked Satan for inspiring his portrayal of Dick Cheney at the Golden Globes, he not only gained the fondness of the Church of Satan, but also expressed how McKay’s film is problematic. He takes a very easy target and, and with a complete lack of nuance, depicts Cheney as the most demonic figure in modern American history, responsible for the war in Iraq, the torture of prisoners and numerous other crimes against humanity. Despite Bale's convincing physical transformation into the powerful politician and the humorous etudes of the actors in supporting roles (though humorous in a way similar to the celebrity cameos in Anchorman), this is a one-dimensional portrait of a diabolical figure without any psychological depth and tells us nothing that we wouldn’t already know. Furthermore, it is an ugly, dull film with mundane direction and, most importantly – unlike The Big Short, which used the same alienating procedures much more systematically – it is not entertaining. The elitist condescension to viewers who clearly would not enjoy Vice (the girl in the intertitle scene, telling her friend how she looks forward to the next instalment of Fast & Furious) is, despite how clever the film pretends to be, really stupid. 50%