Reviews (935)

Cold Case Hammarskjöld (2019)

Documentary phenomenon. A Danish journalist embarks on an investigation of the strange circumstances of the death of a former secretary general of the United Nations. In doing so, he encounters a devilish plan that is reminiscent of a second-rate horror movie, including secret laboratories in the African jungle, assassinations and “vaccines” with HIV. The uncovering of a vast conspiratorial network, in which the CIA, several European countries and multinational corporations are clearly involved and which may have had a major impact on the state of contemporary Africa, is framed by director Mads Brügger's attempt to give the narrative some kind of consistent form. That appears to be impossible, however, due to the large number of unreliable witnesses (of which there are many more than credible materials). In parallel with the gripping detective work that uncovers the conspiracy, we also see the journalist’s growing frustration with the fact that the truth continues to elude him and his original attempt to cope with the impossibility of separating fact from fiction by, on the one hand, continuously reflecting on what he has (not) discovered and, on the other hand, through animated sequences, which are admittedly unreliable reconstructions. If you enjoy highly complex spy thrillers with dozens of intricately connected characters in which understanding of the complex structure and links between the individual involved parties is of greater importance than clear and definitive conclusions, you will, like me, hold your breath for two hours. 90%

Mindhunter - Season 2 (2019) (season)

“I’ve got Manson for you.” After spending nine hours with the second season of Mindhunter, I would need a long walk, a glass of hard alcohol or – like Holden Ford – a few Valium pills. Even though we see perhaps even less explicit violence than in the first season, the atmosphere of some scenes is unbearably intense thanks to the ability of the series’ creators to stimulate our imagination. Again, this is a perfectly anti-climactic detective show and a masterclass in directing long, claustrophobic, minutely edited interviews (the second episode offers one of the best, with an attack victim) whose dynamics change based on the knowledge and experience of the individual speakers (a black detective understands a social outcast better than the privileged Ford; Wendy Carr exploits the fact that she is a lesbian when interrogating the perpetrator of homophobic murders...). The certain mechanical nature of such dialogue is a pity, as it works repeatedly with the fact that the particular knowledge possessed by one of the interrogators due to his or her character/personal situation will change the course of the given interview’s development. ___ At the same time, the narrative gradually focuses increasingly on one specific case (for which, however, other analysed cases provide valuable “study” material), connecting several key motifs of the entire series (all of which are linked to the crimes of the Manson Family, which will also be discussed) – the permeation of violence into American households (murder of children/murderous children), racially motivated murders, the media’s creation of a mythology of serial killers and contribution to the fact that those killers then inspire others (in this respect, the series is somewhat inconsistent – on the one hand, it is as if the facts about BTK are inadvertently withheld from us and our desire to learn details about him is intentionally left unsatisfied, but at the same time, nearly the entire episode is focused on Manson and Tex Watson, who are not important for the main story. ___ The second season is compelling also thanks to the more complicated relationships between the protagonists, who find it increasingly difficult to keep their professional and personal lives separate and to carry on ordinary conversations during which they do not attempt to outsmart the other party (as in interrogations) and thus confirm their intellectual superiority. Though in the second season they move in open space and broad daylight more frequently than in cramped interiors, their possibilities of where to continue onward in life are increasingly limited. The feeling of being boxed in is deepened due to the more thorough (psycho)analysis of the central trio. ___ In terms of craft and storytelling, Mindhunter is qualitatively the most mature and balanced series of the year so far…even though you probably will not be able to listen to Peter Gabriel for a while without thinking about autoerotic asphyxiation.

Our Man Flint (1966)

“Anti-American eagle. It’s diabolical.” Our Man Flint is a unique parody containing fewer humorous lines and situations than any of the early Bond films (as well as, for example, Moonraker, which though meant seriously, still remains a much more entertaining bit of tripe). Agent Flint could easily be a member of the same club as Her Majesty’s agent. Though he shows less respect for his superiors, possesses more liberalism in matters of female emancipation (hippie laxness as opposed to Bond’s conservatism, but put under a bit of pressure by a feminist threat in the sequel) and behaves in a more mature manner than Bond (definitely with fewer one-liners), he is the equal of 007 in terms of language skills, breadth of interests (among other things, he studies ballet and understands the language of dolphins) and physical performance. However, the film itself lags far behind the Bond films. It has a tiringly slow pace due to long padding shots. The scenes, though Bondishly set in luxury restaurants, modern research laboratories and smoky bars with exotic dancers, lack style and, furthermore, give the impression of being cheap. It is often not even possible to know in which country the action is taking place. With great effort, Jerry Goldsmith, who is audibly interested in the central Bond motif, and James Coburn, who handled fights against Connery himself and in unedited shots, eventually managed to drag the film out of the realm of obscurity. Though the sequel contains a comparable number of long, empty scenes (especially with technological toys) and focuses too much attention on characters other than Flint, it obviously had a larger budget and it is more apparent that it was intended to be a comedy. 50%

On a Clear Day You Can See Forever (1970)

With the Barbra Streisand’s singing and cleavage in the lead roles, On a Clear Day You Can See Forever is a colourful film on the surface, but rather gives a grey impression. The last project made fully under director Vincente Minnelli's control (he later fought to no avail with American International Pictures over the final form of the subsequent A Matter of Time), the film fails to conceal the fact that behind it is a man who longs in vain to understand rapidly changing times. With respect to the period in which it was made, which favoured more aggressive filmmakers, the style is very sedentary with a slow pace and modest in its approach to the topic of love. Not even Jack Nicholson, apparently cast as the fashionable mascot of hippie films of the era, is able to give it any vitality. The only livelier singing performance (starting on the roof of a skyscraper) comes at the moment when most viewers, without a weakness for the golden era of Hollywood musicals, have either left or fallen asleep. 50%

Once Upon a Time in Hollywood (2019)

As Tarantino stated in an interview with Time magazine, “I thought, we don’t need a story. They're the story.” It does not matter at all that Once Upon a Time in Hollywood is less spectacular that Tarantino’s previous films (with the exception of Jackie Brown, with which it shares a slow pace, melancholic mood and greater focus on the characters). More than on perfectly timed jokes, memorable one-liners, unexpected twists and building tension in long sequences, the film relies on the characters’ emotions (or what – like Sharon Tate – they symbolise), construction of a fictional world, the period atmosphere and the actors’ charisma. At the same time, it has an inventive three-act structure that serves well both as an evocation of the late 1960s in Los Angeles and another of Tarantino’s discussions over film/real violence and cinema as a means of living multiple lives in parallel and bringing that which has perished back to life. SPOILERS FOLLOW! From great details to greatness as a whole. From a poster-boy hero to a hero who saves actual lives. From Nazisploitation to exploitation inspired by the Manson Family. A recollection of an era when American films became more artsy (The Graduate, Easy Rider) under the influence of European cinema and more violent under the influence of the Vietnam War and turmoil on the streets (Bonnie and Clyde, The Wild Bunch). Tarantino’s use of those techniques (for example, jump cuts and long, hopeless drives as in films of the French New Wave) recalls the given period not only through music, set design and costumes, but also in formal terms. Conversely, classic Hollywood is represented by two burnt-out cowboys who, like the long-serving bosses of the major studios, do not understand young “fucking hippies” and, in the narrative that is newly taking shape, are condemned to play the roles of villains, with which they have no intention of reconciling themselves. However, the end of their era is inevitable. The protagonist of the cowboy movie that Rick reads is taken out of action roughly halfway through the story due to a hip injury. Cliff is likewise injured at the end of the film. Thus, at the end of Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, it seems that we are only halfway through Cliff and Rick’s story. Their fate is already sealed and though the conclusion of the film, while rectifying one tragedy, may seem to be a happy ending, we know that the heroes do not come out of it well (the fact that Trudi Fraser/Jodie Foster reads a biography of the, for her, brilliant Walt Disney, whose racism and anti-Semitism will begin to be addressed many years later, has a similar maliciousness). In my opinion, the key to the cohesiveness of the narrative and understanding of the story lies in the blending together or, more appositely, doubling of the individual planes of this fictional world and their relationship to actual historical events that play a significant role in shaping our expectations and emotional response. We see Sharon Tate as she was depicted in period promotional videos and photographs (the fact that someone is looking at her, amplifying her unreachability, is accentuated throughout the film, though particularly during the Playboy party, when McQueen comments on her from afar). In the only scene where Sharon herself is watching, we actually watch Margot Robbie, admiring her murdered acting colleague on the screen. Cliff, peculiarly behind the movie screen (of a drive-in cinema), represents a truer version of Rick, as he endures actual blows for Rick and does the work that makes it possible for him to exist in the world of film and television (if he hadn’t repaired the television antenna, they would not be able to watch Rick’s cameo at the FBI). The heroes exist through stories in which they also play stories told about them, which – this is essential for Tarantino’s narrative concept – we do not always know whether they are true (did Cliff kill his wife or not?). Lines delivered in the context of a role have an impact on what happens in the characters’ lives (Rick as DeCoteau tells Luke Perry’s character that he will send his man to his ranch – we subsequently see Cliff coming to Spahn Ranch). The climax of breaking down the boundaries between the real and the possible is Cliff’s encounter with a trio of murderers, whose genuineness he doubts under the influence of LSD. His dog, which is basically the only one that does not play any role, but just simply is (a dog), has no doubts and will do the lion’s share of the work in eliminating the intruders. The relationship between film and reality, the actor and his role, and violence and its representation in the media has always fascinated Tarantino, at least as much as women’s feet. This time, he plays with the transitions between one and the other perhaps even more ingeniously than ever before, and even after two viewings, I still do not feel (not by a long shot) that I would be able to grasp and uncover everything that the film has to offer. 90%

Fast & Furious Presents: Hobbs & Shaw (2019)

Hobbs & Shaw is this year’s biggest guilty pleasure thanks to the ingenious use of parallel editing (the duality of the introductory sequence reminded me of Hitchcock’s Strangers on a Train), Vanessa Kirby and the quoting of Nietzsche. The film becomes doubly entertaining when you notice how it reflects the career development and media image of both protagonists: Dwayne Johnson as a Samoan warrior who immediately enchants everyone with his charisma and Jason Statham as an elegant British criminal who once did a job in Italy. In the context of changes in the action genre, Hobbs & Shaw is characterised both by a distinctive female lead and by its approximation of comic-book films featuring teams of superheroes. Idris Elba plays a villain who has high-tech toys like Iron Man and refers to himself as a black Superman, while Johnson and Statham are essentially indestructible superheroes. Of course, success is only achievable through cooperation, not individually. Thanks to the emphasis on family relationships, which the filmmakers brought to Hobbs & Shaw from previous instalments of the Fast & Furious franchise, this play on sentimentality does not come across as fake, in contrast to the bombastic action. On the contrary, beyond the exploding factories, flying cars and other mechanically and precisely managed over-the-top situations, it ensures that you are aware of understandable human emotions and values with which the viewer can identify. From the perspective of the genre’s history (and the filmic representation of masculinity), it is a stimulating mix of bluntly straightforward, hypermasculine ’80s action, ’90s self-ironic postmodernism and a family-oriented comic-book blockbuster. 80%

Knock Down the House (2019)

This documentary illustrates the problems of today’s America and the Democratic politicians who decided to solve them. Unlike their rivals on both sides of the political spectrum, they intend to do that by actually listening to the working class, to people who are resentful of the fact that no one is fighting for them. The filmmakers focus the most attention on a former waitress from the Bronx who became a congresswoman due not only to her stunning charisma, high intelligence and moral integrity, but also to her clear vision for the future. Better than the old-guard Democrats who chiefly want to hold on to power (and lack the energy to implement real changes), she understood that Trump’s intimidation tactics do not make a political platform. It is quite understandable that Alexandria (“the Great”) Ocasio-Cortez and her touching and inspiring life story (after her father died when she was nineteen, she left a non-profit and began working eighteen-hour shifts at a bar to support her family), thanks to which you will believe that change for the better is still possible, occupy the greater share of screen time (from which Netflix duly benefited when promoting the film). At the same time, it is regrettable that this documentary does not fulfil its initial promise to provide a closer look at the environment of American politics from the perspective of women. Even without striving for timelessness, however, it is a film that will fill with enthusiasm (at least) everyone who is a socialist, feminist and not a complete nihilist. 80%

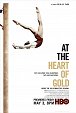

At the Heart of Gold: Inside the USA Gymnastics Scandal (2019)

Not long after Leaving Neverland, HBO aired another outstanding documentary, this time examining a case of sexual abuse of children and adolescents perpetrated over the course of many years. Larry Nassar exploited his position as a doctor for the United States national gymnastics team for more than twenty years. He “treated” back pain and other problems by, among other things, inserting his fingers into the vaginas of young gymnasts. Often in the presence of their parents, which reinforced in the girls the belief that, as a doctor, he knew what he was doing and was helping them to continue to perform at the highest possible level and to earn money from sponsors (“He was a doctor. He must have had a reason for doing that.”). ___ The aggressiveness of his "vaginal treatment" increased with the age of the athletes, who believed that he wanted to help them, because, unlike their despotic coaches, they found psychological support and understanding in him (with regard to this topic, I also recommend the Polish documentary Over the Limit). The cooperation of Nassar’s colleagues from the ranks of coaches and experts at the university where he worked contributed to the fact that his behaviour was long concealed and downplayed and, before he was sentenced to 175 years behind bars, that more than 300 women became his victims. ___ His friends and members of the local community did not want to damage his reputation, or rather did not believe that he would be capable of doing such a thing, as it did not correspond to his image as a nice person and respected medical authority. Rather, doubts were raised about the testimonies of the girls, who in the end felt guilty for telling someone about the harassment and thus imperilling Nassar’s reputation. Through the open testimonies of individual gymnasts and their parents, as well as of experts, the documentary describes not only the tactics used by the sexual predator and the psychological trauma of the victims (which in some cases is exacerbated by disruption of family relationships because the parents did not believe their daughters), but also the culture of sexual harassment fostered in part by numerous institutions (including the US Olympic Committee). On the one hand, there is the fear that accompanies the idea of speaking out against an influential person, while on the other hand, there is strong mistrust. In such an atmosphere and under those conditions, it is not enough to merely talk about it, which is painful in and of itself. 80%

A White, White Day (2019)

A White, White Day is an exceptionally compelling festival slow burner, thanks especially to the raw lyrical involvement of the breathtaking Icelandic countryside, the natural actors and the way Pálmason works with (Scandinavian) crime-film conventions. The film has a detective-movie structure due to the fact that the protagonist applies the modus operandi learned during his police service to address his own suffering. The strive to find and apprehend perpetrators. The problem lies in the fact that no particular person committed the crime that we see in the prologue (at most, Ingimundur himself was an accomplice, if it was a suicide and not an accident). Therefore, the protagonist essentially has to create a perpetrator in order to have something to solve. In the tradition of art cinema, particularly the inner world of the depressed widower is addressed; his disconnection from his own emotions and the world around him is best illustrated by the transformation of his relationship with his eight-year-old granddaughter. He first merely teases her and then scares her with a fictitious story about a stolen liver (which is connected with the key motif of the dead coming back to life, which is “resolved” in the last scene) and finally terrifies her with his own real behaviour. Besides the fine work with motifs (for example, the constant elimination of obstacles, from bloodstains to stones on the path, recalling unaddressed trauma), I also admired the certainty with which Pálmason “builds” long shots of tens of seconds (perhaps even a few minutes) with long segments of dialogue, complex emotions and a lot of action (and possibilities when something could go wrong). A White, White Day is a simple story told in a captivating manner with a tremendous emotional impact. 90%

Midsommar (2019)

Midsommar is a film that will best serve people who are seeking inspiration for a very spectacular way to break up. Aster again lags behind his own ambitions. Midsommar ostentatiously gives the impression that it wants to be an essential contribution to the horror genre. However, the long runtime, slowness and seriousness emanating from the grandiose filming of everyday scenes (camera crane FTW!) and the coldly methodical, mechanically timed editing do not guarantee great depth of thought or psychology (the comparison with Bergman, who did not pretend to be enigmatic, is laughable). When you shoot a psychological horror movie and let the actors ham it up and the characters behave like idiots who do not mind the fact that people are disappearing around them, you pull the rug out from under yourself. In the final third of the film, it is as if Aster is so attached to his effort to build tension that he completely forgets to develop the banal, straightforwardly told story and to concern himself with whether the characters’ actions are consistent. Though noteworthy from an anthropological point of view and nourishing for interpretive adventurers, the attempt to pound into our head with every shot the fact that something scary is about to happen (which is paradoxically less effective than subtler hints would be) and that we are watching a tremendously sophisticated horror film becomes increasingly annoying as the minutes drag by. I could much better imagine Midsommar as a musical comedy (it is actually not far from being just that, though not intentionally) about a group of doped-up flower children singing and dancing in a meadow, wearing animal costumes and familiarising themselves with a foreign culture and cuisine, including, among other things, meat pie with baked female pubic hair. Ari Aster is not a bad director and he knows how to create a dense atmosphere in individual scenes. He would just be better served by considering what is enough. 70%